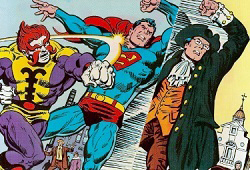

Cover art by Bob Oksner

The alien Karb-Brak has been banished to Earth from his own world, located over a million light-years away in the Andromeda Galaxy. On that home planet, everyone has superpowers similar to Superman. It turns out, however, that Karm-Brak is allergic to those powers and is sent to Earth so that he could survive on a new planet as opposed to die on his old. There was one slight problem – Karm-Brak is likewise allergic to Superman. He thus reprograms the Man of Steel into believing that he is a newspaper reporter for Benjamin Franklin and sends him back in time to colonial America.

“Witness, readers, one of the most famous scenes in the annals of American history – the signing of the Declaration of Independence!” Action Comics #463 – published to coincide with the American Bicentennial in 1976 – exclaims on its opening page. “But wait! Something is wrong with this picture! Superman had nothing to do with this historic document… or did he?” The “picture” in question is an illustrated replica of John Trumbull’s famed oil painting “Declaration of Independence,” only Superman is standing off to the side of John Adams.

Trumball told Thomas Jefferson of his plans to create a series of paintings depicting the major battles of the American Revolution when they were both in Paris during the early 1780s. Jefferson not only liked the idea but suggested that the Declaration of Independence be immortalized on canvas as well. Trumball spent the next few years researching members of the Second Continental Congress before painting the iconic twelve-foot by eighteen-foot painting that currently hangs in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Instead of the signing of the Declaration of Independence as many believe, however, John Trumball’s work instead depicts Thomas Jefferson presenting the Second Continental Congress with a draft of the Declaration created by a five-person committee, whose members stand beside Jefferson.

For historian Tom McMillan, confusion surrounding Trumball’s Declaration of Independence is just one of the many misperceptions regarding the famed document. To set the record straight, McMillan wrote The Year That Made America: From Rebellion to Independence, 1775–1776 – published in 2025 – which tells the story of not only the Declaration of Independence but events immediately before and after the Second Continental Congress voted for independence from Great Britain.

In Action Comics #463, Clark Kent finds himself employed by the Pennsylvania Gazette and editor Benjamin Franklin as opposed to Perry White and the Daily Planet. “As you well know, my distinguished colleagues and I are voting on the declaration this afternoon at Independence Hall,” the bespectacled Founding Father says to his reporter. “And I want you there to chronicle the event.”

Clark Kent immediately sets out for Independence Hall. On the way, he bumps into John Hancock, who exclaims, “Today is the monumental day!” Before the conversation can progress further, a pair of horses pulling a carriage become frightened and race out of control. Both Kent and Hancock chase after them, but only one is able to not only catch up with the carriage but tackle the horses to the ground. John Hancock notices a puddle of mud on the road and rationalizes that the horses simply slipped. Kent, however, is not convinced.

As he continues his journey, Clark Kent notices a trio of men huddled together in an alley. They are in fact traitors to the cause of independence and secretly working for King George III of England. Believing that Kent overheard their plans, they throw punches at his jaw and torso, as well as attack him with a solid brass lamp base. The still brainwashed Man of Steel is impervious, however, causing the men to quickly run away.

As Clark Kent puzzles over his ability to chase down stampeding horse and absorb blows from British spies, additional features of his Superman persona become evident as well. First, his x-ray vision spots the Declaration of Independence inside an empty Independence Hall, waiting to be signed. He also sees the three men he earlier encountered tunneling into the building. His super-hearing likewise kicks in, and he can now hear their plans to steal the Declaration for King George, who is paying them to hand deliver the document to him in England.

On July 1, 1776, the Second Continental Congress met at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia – now known as Independence Hall – to discuss independence. After a nine hour debate, a preliminary vote was taken. Nine of the thirteen colonies were in favor, two against, and one deadlocked. The delegates from the remaining colony, New York, were not yet authorized to vote on the matter, so there was one abstention as well.

Although a clear victory for those in favor of independence, it was not unanimous, so it was decided to hold off on a formal vote until the next day. The delegates then retreated to a nearby tavern. No one knows what was said over libations, but the vote taken on July 2 resulted in twelve colonies being in favor of independence and one abstention (New York would make it unanimous on July 9). South Carolina had been persuaded to switch from “no” to “yes,” while a third delegate arrived from Delaware to break that state’s deadlock.

John Dickenson and Robert Morrise of Pennsylvania were still against independence but refrained from voting, resulting in Pennsylvania likewise switching to “yes.” A small blurb appeared in that evening’s Pennsylvania Evening Post that simply read, “This day, the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.”

John Adams wrote a letter to his wife Abigail afterwards in which he declared, “The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe it will be celebrated by succeeding Generations as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

As Tom McMillan notes in The Year that Made America, “Barely twenty-four hours after the historic vote, (John) Adams was convinced that Americans already had their Independence Day, the ‘Second of July.’ He was correct, but popular culture remembers it differently.”

With his memories now fully recovered, Superman flies into the tunnel underneath Independence Hall in hot pursuit of the three thieves who have just stolen the Declaration of Independence. He uses his super breath to send them tumbling out the other side and into the air, then whisks them northward and drops them at the feet of General George Washington.

“At that very moment, many miles away, fifty-six distinguished men are filing into Independence Hall for an event that will lay the foundation for the greatest nation on Earth,” Action Comics #463 declares. “And as Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, John Adams, and the rest of the Founding Fathers enter the hallowed hall, once again a blurred figure whizzes by too fast to be seen but not too fast to return the about-to-be signed Declaration of Independence to its rightful place without a second to spare. The vote is taken… the Declaration is adopted… and John Hancock steps up to adorn the fateful document with his flamboyant signature on this Fourth of July 1776.”

Although the Second Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2, there still was the matter of making the decision public. The Congress previously established a five-person committee consisting of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman to draft a declaration and reconvened on July 3 to debate and edit the proposed document. What later became known as the Declaration of Independence was then approved the following day and sent to the printer unsigned – signatures weren’t added until the following month. At the top of the document, the printer engraved the words, “In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776.”

One year later, the July 2 anniversary of the vote for independence came and went without any recognition by the Second Continental Congress. To correct the oversight, preparations were quickly made for a July 4 celebration instead. Even John Adams got caught up in the moment, writing to his daughter Nabby, “Yesterday, being the anniversary of American Independence, was celebrated with a festivity and ceremony becoming the occasion.” When both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson later passed away on July 4, 1827, any lingering doubts about which day would be recognized as a national holiday had been erased.

Just ask Superman.

Anthony Letizia