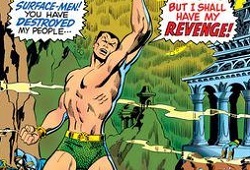

Cover art by Marie Severin, Sal Buscema, and Artie Simek

As Namor the Sub-Mariner explores the underwater boundaries of his fabled kingdom of Atlantis in Sub-Mariner #25, he comes across the dead bodies of numerous Atlantean sentries. The cause of their demise is likewise visible, discarded canisters intended for chemical warfare by the U.S. government. Although falling short of declaring war on the “air breathers,” Namor is determined to make his anger known nonetheless.

A ship bound for Great Britain is thus ordered to detour around the waters of Atlantis. When the captain refuses, the ship is incapacitated by the Sub-Mariner’s followers and towed back to its port of origin. Additional ships are challenged in the same manner – some turn around, others allow themselves to be boarded and searched for weapons, and others attempt to fight but lose the resulting battle.

Back in Atlantis, Namor’s advisers are concerned. The Sub-Mariner has stated over-and-over again that he has no intentions of going to war, but his actions appear to be plunging Atlantis in that very direction. If his own people believe this, Namor realizes, then the air-breathers must think so as well.

“Do you not see, my friends, that I had to prove I was ready for war so the surface-men would listen when I spoke of peace?” he tells them before heading to New York City and a visit to the United Nations.

On January 28, 1969 – a mere fifteen months earlier – an environmental disaster struck in the real world. A Union Oil subcontractor had recently begun drilling into the Outer Continental Shelf, just five mile off the coast of the Southern California city of Santa Barbara. After fourteen days of penetrating the ocean floor, the crew began removing pipe from the hole that had been created. Their actions caused subterranean artesian pressure to be released, sending mud and natural gas upward until both were spewing from the open wellhead. When the requisite blowout preventer proved ineffective, the crew improvised, dropping a pressure gauge into the hole to seal it.

As Teresa Sabol Spezio explains in her 2018 book, Slick Policy: Environmental and Science Policy in the Aftermath of the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, the sealing of the well caused the still present pressure to find another way to vent, and the fissures of a nearby underwater fault line provided the means. Within a matter of hours, oil began spewing out of those fissures, dumping anywhere from 22,000 to 220,000 gallons of oil into the Pacific Ocean each day for the next ten days. The estimate was difficult to accurately gauge because unlike oil spills that originate from one specific source, the Santa Barbara spill had multiple sources along the fault line.

Union Oil and the federal government had two immediate objectives – first, the spill had to be stopped, and second, the oil that was already spreading needed contained and collected. Oil and water do not mix, and under ideal circumstances, the oil remains on top of the water for easy retrieval. Within an ocean environment, however, winds, currents, and waves force the two substances to interact, making it much more difficult to isolate the oil.

To make matters worse, Union Oil lacked the necessary equipment and workforce to handle such a disaster, while the federal government had always relied on the oil industry to manage offshore drilling with minimal oversight on its part. Since the drilling platform was one of the first constructed along the Pacific shoreline, Union Oil came up empty when it tried to find assistance in California, eventually turning to Gulf States like Texas and Louisiana. This resulted in even more delays as both equipment and skilled workers had to be transported to the West Coast.

Although the oil didn’t immediately reach the shore, it wasn’t long before dead and dying oil-soaked birds began appearing on the Santa Barbara beach. Fearing a media frenzy, Union Oil immediately opened a rehabilitation center to rescue and clean the birds, while the Child’s Estate Zoo provided a contingent of volunteers to assist. As the spill continued and got closer to the beaches, the national media coverage began to escalate. With dead birds on the sand, the winds changing direction and a storm on the horizon, television networks now had the visuals needed to effectively transmit the growing disaster coast-to-coast.

If the gauge dropped into the well after its initial blowout was dislodged, mud could then be pumped into the hole to equilibrate the oil pressure and stop the leakage from the fissures. It took six full days for the gauge to finally be removed, and by day seven, 165,000 gallons of mud had been pumped into the hole, slowing the leaking oil but not stopping it. It wasn’t until day ten of the crisis – after pumping another thirteen thousand barrels of mud into the well – that the leakage finally subsided. Cement was then poured on top of the mud, permanently sealing the well and ending the immediate danger.

Back in the Marvel Comics Universe, the Sub-Mariner flies over the skies of New York City towards the United Nations. Someone in the crowd below exclaims, “It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s Mr. Spock!” Luckily a television news reporter is there to correct them, telling those watching at home, “It’s actually Prince Namor of Atlantis, accompanied by the girl Dorma, who’s landing on the U.N. Plaza. An anxious world is breathlessly waiting to see what happens when he does.”

After easily disarming the police sent to stop him, Namor makes his way onto the floor of the General Assembly. “We’ll listen for five minutes, Namor – but only because you’re the leader of a country,” one of the delegates tells him. “When you’ve had your say, you can get out.”

Namor begins by demanding that Atlantis be recognized as a sovereign country and admitted to the United Nations. The uproar is immediate, as members of the U.N. begin calling Atlantis a “menace to the entire world.” The Sub-Mariner refers to them as fools in response, especially “after what you have done – and are doing – to the face of an entire planet.”

Before anyone can interrupt, the Sub-Mariner continues. “Is it Atlantis which has callously dropped cans of lethal gas into an ocean, causing needless deaths?” he rhetorically asks. “Is it Atlantis which has beclouded a world with pesticides, whose vile after-effects can turn both land and sea into one vast slaughterhouse? Is it fair Atlantis which has spilled countless gallons of crude petroleum into the seas, causing the near extinction of species after species of wildlife?”

After having vented, Namor next threatens the United Nations. “Kill off each other with your atomic toys if you must,” he says. “But threaten the sea, and you will force us to take action against you!”

The publication of Sub-Mariner #25 coincided with the first Earth Day in April 1970, a little over a year after disaster struck near Santa Barbara. Namor’s warning was echoed by millions of Americans coast-to-coast as a result of the oil spill, raising awareness and launching an environmental movement that has yet to subside. Namor may be a fictional character, but he no doubt would have been pleased that his message was finally heard.

Anthony Letizia