In January 1996, Professor Mark Carnes of Barnard College in New York City was at a crossroads. His previous semester’s course had fallen flat, with students barely grasping the fine details of Plato’s Republic and class discussions containing more moments of silence than actual dialogue. Although Carnes did not realize it at the time, that silence would lead to a new way of teaching – one that relied on role-playing games and collectively became known as Reacting to the Past.

The journey began when Carnes decided to meet with students from the previous semester to get a better handle on why the class had gone awry. Unsure how to answer his query, most reacted as if they enjoyed the class. Eventually Carnes’ frustration boiled over and he told one of the students, “You were bored! I was bored! You could feel the boredom in the room.” After a brief pause, the student replied, “Well, yes. But all classes are sorta boring. Yours was less boring than most.”

Over the summer, Mark Carnes decided on a new approach for his fall 1996 course. Instead of relying solely on lectures, he would insert three “games” modeled after debates – one each month – into the class. The first was based on Plato’s Republic and the question of whether Socrates was guilty of “corrupting the youth of Athens.” Students were divided into two groups, the defenders of Socrates and his prosecutors. Each group met individually and then the trial was reenacted over the course of several classes.

Carnes was pleased with the results. “None of it was all that different from the question-response structure of other seminars,” he explained in his 2014 book, Minds on Fire: How Role-Immersion Games Transform College. “This was just a slightly more stylized way of accomplishing the same end. Many teachers had held mock trials of Socrates. Many students had participated in structured debates for Model UN. My class was not in the least bit special. But several weeks later things careened in an unexpected direction.”

The second game was set in the Forbidden City of Beijing during the Ming Dynasty and the struggle between Confucian purists and advisors to the Emperor Wanli who were more inclined to political interpretations of the philosopher’s teachings. Students read The Analects of Confucius and were again divided into two groups. The winner would be whichever group convinced Wanli to take their point of view.

Two students – Purvi Mehta and Fiza Quraishi – were randomly chosen to portray the emperor and his first minister. Carnes thought the first session went well, later referring to it as “lighthearted and fun.” Afterwards, however, Mehta and Quraishi complained that no one in the class was taking it seriously.

“Confucius believed that ritual could teach behavior,” Carnes replied. “He said that if you perform mourning rituals, you’re more likely to feel grief; if you bow to a superior, you’re more likely to feel deference. Maybe you should try that.”

So they did. At the next class, the Emperor Wanli was initially absent. First Minister Fiza Quraishi told her classmates that she was displeased, that scholars were expected to treat the emperor with respect. No more side conversations or jokes would be tolerated. “You can speak only when I say so,” Quraishi continued. “If you fail to do this, I’ll have you removed. And remember: your grade depends on class participation and your grade will suffer.”

One of the students shouted, “She can’t do that!” and looked at Carnes, who simply replied, “Sure she can. She’s the top minister.” When Purvi Mehta then entered the classroom as the Emperor Wanli, everyone rose, including the student who had protested.

“Gradually the tone of the class shifted,” Mark Carnes wrote in Minds on Fire. “Students deferred to Fiza and emulated her seriousness. Critics of the emperor lowered their voice and couched their barbs in flowery metaphors: (‘Oh, worthy and most esteemed emperor’). Confucian precepts that in other years I had to tweeze out of students now blossomed in profusion. Shy students spoke. The debate, though conducted almost in whispers, acquired a strange, sharp edge. No class I had seen even vaguely resembled this one. Never had I ‘taught’ a class without saying a word. Never had students been so engaged and in such a weird way.”

As the transformation continued with each subsequent class, Carnes decided to invite Judith Shapiro, the newly installed president of Barnard College, to pay a visit. Purvi Mehta and Fiza Quraishi had spent a mere weekend of research to devise their takeover of the game and give it a new direction. Carnes and Shapiro now wondered what kind of similar games could be created by committed scholars over the course of several months. Shapiro gave Carnes the green light to find out.

The result was Reacting to the Past, a collection of historical role-playing games designed by academics for use in college classrooms. Although the subsequent nonprofit Reacting Consortium is located at Barnard College, the games themselves are designed and used by college professors across the country. By the end of 2024, there were over seventy-five Reacting to the Past games available, covering not only history but politics, religion, journalism, economics, and STEM.

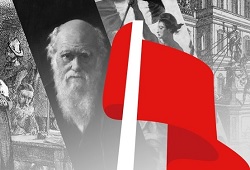

Should the Royal Society award Charles Darwin the Copley Medal for The Origin of Species? Should Galileo Galilei be found guilty of heresy for Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems? The Watergate scandal created a constitutional crisis in the early 1970s – what steps could political leaders in Washington take to minimize the damage? And when London theaters closed in 1592 because of the Bubonic plague, which playwright should be spotlighted when they reopened, Christopher Marlowe or William Shakespeare?

“All of these games, they’re driven by ideas and especially by the clash of ideas, so sources are of course at the center of this,” Emily Fisher Gray, a professor at Norwich University, explained at the 2023 American Historical Association conference. “Students take on a particular identity of a real person in history and then they have to solve problems, real problems in history. In so doing, they’re doing public speaking, both formal and informal public speaking. They’re doing writing, both formal and informal writing. They’re doing a lot of critical thinking, they’re involved in a lot of persuasion. They have to use leadership. A lot of us at our universities talk about leadership in some sort of abstract way. In Reacting, the professor sits in the back of the class and the students are literally leading each other in the front of the class. So it’s real leadership. And then it brings a sense of historical empathy – no longer is history just a series of events that just show up in your textbook.”

Even more impressive than the games are the student reactions. For instance, when Paul Fessler decided to use Reacting to the Past to teach the French Revolution as part of his Western Civilization class at Dordt College in Sioux City, Iowa, he soon received an unusual request from the students – could the 8 a.m. class begin thirty minutes earlier?

“Keep in mind that we’d already lost a lot of sleep in playing the game,” one of the students later told Mark Carnes. “We read more in the weeks of the game than we had at any time in the class. We plowed through the game manual, our history texts, Rousseau, you name it. We spent hours writing articles. I spent several all-nighters editing my faction’s newspapers, and the other editors did too. It had become more than a class to us at that point. The early-morning sessions were the only way to honor the sacrifices that everybody had made.”

Other professors from across the country have similar stories – classes with perfect attendance for the entire semester. Unregistered students taking the course and doing the work without getting any academic credit. Students who have already taken the course volunteering to take on roles within the game, or even auditing the course just so that they can play the game again.

“Nearly everywhere, the results are the same,” Mark Carnes writes in Minds On Fire. “Students work harder than anyone can recall. Students rarely miss class and faculty look forward to it. No one calls these classes ‘Sorta boring.”’

In short, Reacting to the Past is a win-win-win for students, professors, and – most especially – institutes of higher education as well.

Anthony Letizia