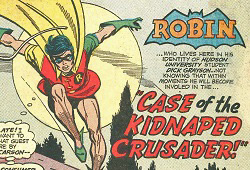

Art by Bob Brown and Frank McLaughlin

At Hudson State University, Dick Grayson – donning his superhero attire as Robin – races over the rooftops. “It’s late,” he tells himself. “I don’t want to miss that guest lecture by Tom Carson, the consumer advocate who’s gotten the government to pass new safety laws for cars.”

As he gets closer to the lecture hall, Robin flies through an open window and changes into his Dick Grayson persona. Despite taking the highroad as Robin as opposed to walking as Grayson, the Hudson State University student arrives just as Carson is exiting the building. Fortunately, the superhero will be on hand for what transpires next in the “Case of the Kidnapped Crusader,” published in 1973 in the back pages of Batman #249.

During the 1960s, Ralph Nader emerged as the leading crusader for consumer rights in the United States. A graduate of Harvard Law School, Nader believed that every American had the right to safely use any product that they purchased. “My job is to bring issues out in the open, where they cannot be ignored,” Nader told Time magazine in a December 12, 1969, cover story. “There is a revolt against the aristocratic uses of technology and a demand for democratic uses. We have got to know what we are doing to ourselves. Life can be – and is being – eroded.”

In 1965, Nader released Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile. The book was not only a best seller but started a debate in the country regarding automobile safety features, leading to the creation of the Unted States Department of Transportation and passing of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which mandated the installation of seat belts in all new cars.

One of the chapters in Unsafe at Any Speed included a devastating critique of the Chevrolet Corvair, which was manufactured by General Motors. Sales for the vehicle quickly dropped by 93% afterwards. The automobile industry giant was not happy, and CEO James Roche admitted under oath at a U.S. Senate hearing in March 1966 that GM had hired a private investigator to tap Nader’s phone and gather damaging information about him. Nader sued General Motors for invasion of privacy, resulting in a $425,000 settlement in his favor.

Ralph Nader used the money to fund further consumer advocacy efforts. His next feat was to enlist seven volunteer law students – nicknamed “Nader’s Raiders” – to evaluate the Federal Trade Commission, leading to an investigation of the organization by the American Bar Association. The next year, slightly over one hundred law, engineering, and medical students were likewise hired as Nader Raiders. Over 700 applications were received from students in Texas alone for an internship that lasted only ten weeks and paid between $500 and $1000.

Tom Carson’s visit to Hudson State University involves more than a guest lecture as he has also agreed to a test ride an experimental car designed by the school’s engineering department. Looking for an interview with Carson, the editor of the student newspaper – Starly Evans – pulled some strings and got assigned as the consumer advocate’s driver.

“Starly?” Dick Grayson asks himself upon hearing the news. “He drives like a maniac.”

Tom Carson has more to worry about than Starly Evans’s driving skills as an explosion rocks the vehicle as it circles the track. The car skids to a halt as smoke spills out but fortunately the driver is safe, as well as the car. The same cannot be said for Carson, who has disappeared from the vehicle – as one student notes – in a puff of smoke.

Dick Grayson decides that the detective skills of Robin are needed and dashes off to change clothes. In the meantime, the police have arrived on the scene. Instead of asking questions or looking for Tom Carson, they simply drive away in the car. Robin blocks their exit with his motorcycle and asks to inspect the vehicle, and the police agree to allow him. His search, however, comes up empty.

“The most logical explanation is that someone nabbed Carson under cover of the smoke, but how did they do it so quickly?” Robin ponders afterwards. Then there’s the matter of the police. “Somehow I have the feeling the cops are in a hurry to carry out their own investigation – in private.”

Ralph Nader’s various campaigns for consumer rights resonated with college students and – just like Tom Carson – the real world consumer crusader made regular appearances on college campuses. In addition to attending Nader’s lectures, students also volunteered at Ralph Nader’s Public Interest Groups, where they conducted research on local business practices, made sure companies weren’t price gauging, and kept track of pollution in the area.

“This is a new form of citizenship,” Nader told Time magazine. “You watch. General Motors will be picketed by young activists against air pollution.”

The legal profession was of particular importance to Ralph Nader. “The best lawyers should be spending their time on the great problems – on water and air pollution, on racial justice, on poverty and juvenile delinquency, on the joke that ordinary rights have become,” he said. “But they are not. They are spending their time defending Geritol, Rice Krispies and the oil-import quota.”

The words were apparently having an effect. Time noted that out of the thirty-nine Harvard Law Review editors set to graduate in June 1970, only one planned on joining Wall Street. A large segment of the remainder intended to work for neighborhood or government agencies, where they could look out for the consumer on the inside.

It was within the halls of Congress, however, that Ralph Nader made his greatest impact. Not only did his advocacy result in the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act in 1966, but the Wholesome Meat Act in 1967 and the Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act, the Radiation Control for Health and Safety Act, and the Wholesale Poultry Products Act in 1968.

Although Nader would later run for President of the United States four times – in 1996 and 2000 as the nominee of the Green Party, the Reform Party in 2004, and then as an independent in 2008 – he told a student at Dick Grayson’s Hudson State University “Never!” when asked if he would ever run for president. The year before, he was true to his word when he declined an offer from Democratic Party nominee George McGovern to join the ticket as vice president.

Before the police drive away, one of them tells Starly Evans that they will want to question him later. At that point, Robin connects the dots – the policemen are imposters and somehow mixed up in the disappearance of Tom Carson. He races after them on his motorcycle and is greeted with gunshots. Realizing he has no alternative, Robin drives in front of their car and suddenly stops. He leaps from his motorcycle just as the car hits it but the two “police officers” are not as lucky.

“No car is going to be ‘super-safe’ unless you put on your seat belt,” the Boy Wonder notes. “They’ll be out long enough for me to check the trunk.” Sure enough, this time Robin discovers a secret compartment containing an unconscious Tom Carson. Robin is able to revive the consumer crusader, as well as take the fake cops to a real police station.

“I’m sure the police will find who’s behind this,” Carson tells Robin afterwards. “I’ve caused trouble for a lot of powerful people lately.” He then adds that he’s late for an appointment in Washington and that Starly Evans has offered to drive him to the airport.

“Personally, I wouldn’t trust Starly’s driving at any speed,” Robin thinks to himself. “But it’s Carson’s problem.”

Anthony Letizia