“The problem of the homeless must be addressed,” Congressional candidate Tom Caywood tells the crowd attending a campaign rally in Seattle. “If we are to make this a great city and a great nation, we must begin by caring for our people. This doesn’t simply mean more shelters. It means a concentrated rehabilitation program to help these people get off the streets and into the mainstream of productive society.”

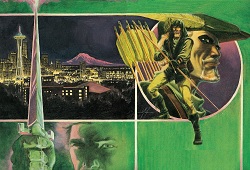

Tom Caywood was not an actual candidate but a fictional politician in writer Mike Grell’s Green Arrow comic book series from the late 1980s and early 1990s. Instead of the usual Star City, Grell placed the DC superhero in Seattle, Washington, and utilized narratives that were more in-tune with the times as opposed to the “supervillain” plots that normally populated comic books. Although unmentioned for the bulk of Mike Grell’s run on Green Arrow, the homeless population of Seattle inevitably made an appearance in a small handful of issues nonetheless.

According to Josephine Ensign in her 2021 book Skid Road: On the Frontier of Health and Homelessness in an American City, Seattle has more homeless than any American city other than New York and Los Angeles. This isn’t a recent development, as the Pacific Northwest – as well as the United States in general – has always had its fair share of people struggling financially and suffering from mental health issues, driving them from their homes and onto the streets as a result.

In the late nineteenth century, for instance, Seattle’s main industries consisted of logging, fishing, agricultural, and coal mining, all of which relied on low-skilled manual labor. The work was seasonal, however, and while many of those workers were transients who only stayed in the region when there were jobs, there were those who remained year-round and were homeless when employment was scarce.

After the Civil War, meanwhile, former soldiers in both the North and the South suffered from what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, and instead of settling down decided to roam the country. Known as hobos, they would hop onboard railroad cars and migrate from city-to-city looking for handouts and the occasional job. The shipbuilding industry had an impact on the homeless of Seattle as well. During the peak years of World War I, an additional 20,000 laborers migrated to the region to work in the shipyards, putting a serious strain on local housing. When the Skinner and Eddy Shipyard lost its federal contracts after the war ended, tens-of-thousands of those workers lost their jobs as a result.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression aggravated the situation not only in Seattle but across the country, leading to shantytowns filled with unemployed workers that were called Hoovervilles – the largest in Seattle stretched over nine-and-a-half acres. The homeless landscape again changed during the 1970s and 80s as more women, families, young adults, and teenage runaways were forced to live on the street. The economy – from lack of jobs to disproportionate salaries – played an obvious role, but so did higher divorce rates and an influx of Vietnam veterans who struggled after their return to the United States.

In Skid Row, Josephine Ensign ties stories of the actual homeless into her general exploration of Seattle’s history, from the city’s first homeless man in 1854, to the Native American daughter of Chief Seattle, to a teenage girl living on the streets during the 1980s. Mike Grell does the same, weaving his own stories of the homeless into Green Arrow, albeit fictional ones.

In one issue, for instance, Green Arrow encounters a young homeless woman named Marianne. “My old man smashed my face into a brick wall when I was 10 just because I didn’t do my chores,” she explains. “When I was 15 he went after my little sister, and I went after him with a baseball bat. I put him in the hospital, and they put me and Sheri in a home for a couple of months. But when my dad got out of the hospital, the sent us back to him. Six months later, Sheri OD’d. She was 13. She was the only reason I stayed.”

Despite her tragic story, Marianne is upbeat and still hopes to someday finish school and become a writer. In the meantime, she has not only found friends within the homeless community but the vendors at Pike Place as well, some of whom give her fruit and vegetables. Her pleasant demeaner also helps attract spare change from passers-by, and she is also not above lifting a few dollars from their pockets. Green Arrow meets others who are homeless through Marianne, including a former boxer who prematurely left the ring and a Vietnam veteran who couldn’t handle the atrocities of war and deserted.

In Green Arrow #67, the murder of a homeless man – a former research chemist who lost his wife and daughter in a car accident – makes the front-page news of the local newspaper. “All anybody ever knew about him was that he used this line about being a drunk,” Marianne tells Green Arrow. “People would give him money because they were tired of being hustled with hard-luck stories. They thought it was a welcome switch to meet an honest man. I knew him most of the time I was on the streets, and I never once saw him take a drink. People always want to believe the worst.”

The murder was not a solitary incident as two other homeless men were recently killed as well. “Why would you?” Marianne replies when Green Arrow says he wasn’t aware of the previous deaths. “They were only street people. But now it’s a serial killing. Some nut with a hammer knocking off anyone is big news. Suddenly the people you walk past day after day without a glance are important because they make good copy on the 6:00 news.”

Real-world Seattle has the distinction of having not one but two serial killers operating in the area during the latter half of the twentieth century. Ted Bundy worked on a hotline operated by the Seattle Crisis Clinic while raping and murdering female students at the University of Washington and other local colleges. He was later arrested in Florida and convicted in 1980. Gary Ridgway – better known as the Green River Killer – embarked on a killing spree in the Seattle region as well, targeting young runaway girls and prostitutes. Unlike Bundy, however, Ridgway was able to avoid arrest for over a decade and wasn’t apprehended until 2001.

“That it took Seattle area police investigators so much longer to identify and arrest Ridgway than it took for Ted Bundy raises the question of whose lives are more important,” Josephine Ensign writes in Skid Road. “The affluent, mainly white, young female college students killed by Bundy or the impoverished, runaway, homeless, prostituted, and more often nonwhite girls and young women killed by Ridgway.”

The Seattle of Green Arrow also had a serial killer targeting prostitutes. The police had a suspect, a man by the name of Harold Gilbert, but could never gather enough evidence to arrest him. When a prostitute named Megan Samuels was murdered by a copycat killer and Gilbert lacked an alibi, Lieutenant James Cameron framed him for the crime. After his conviction, Harold Gilbert confessed to the murders of seventeen prostitutes over a nine-year period to “justify” his death sentence but insisted that he did not kill Samuels.

Flashforward a few years and a new killer – called the Slasher – is on the prowl. Green Arrow suspects he is a Harold Gilbert copycat, and eventually the guilt of having never pursued Megan Samuels’ actual killer forces Cameron to confess his duplicity. Taking up the case himself, Green Arrow pays a visit on the roommate of another victim of the Slasher. “Something happens to one of us, who gives a damn?” she asks the superhero. “Nobody really cares if a whore winds up in an alley with her stomach slashed open. There is no justice for people like us.”

“There is now,” Green Arrow replies.

“Wicked problems like homelessness are best approached by being willing to enter the swamp, to value the role of stories, of a multiplicity of stories, and to nurture the capacity to listen to – and for – them,” Josephine Ensign concludes in Skid Road: On the Frontier of Health and Homelessness in an American City. Sometimes those stories may be fictional, like in the case of Green Arrow, but they help shine the spotlight on neglected issues nonetheless. Others are factual, however, and those recited by Ensign gives voice to the previously voiceless and are even more deserving of being heard as a result.

Anthony Letizia